The 3 Most Important Things We've Learned about Alpine Wine (so far!)

And looking back on Chardonnays of Savoie and Bugey plus a springtime risotto recipe

This month, the Alpine Wine Society turns three! Three years ago, amidst the retreat of the global pandemic and the manic resumption of in-person activities, Julia and I asked ourselves if anyone would want to read a newsletter dedicated to wines from a niche, largely undiscovered wine region. It turns out – yes! We have been thrilled by all of the readers who have found us over the past few years, and delighted to meet so many kindred spirits along the way: winemakers, importers, distributors, retailers, restaurateurs and writers who share a love for what the Alps have to offer, and who continually inspire us with their dedication and passion.

As we’ve acknowledged, there is a lot of uncertainty in the wine world right now. And yet, despite some looming challenges, we operate under the assumption that both great wine and the great peaks will outlast tariffs, neo-Prohibitionism, and frankly, all of us. And so we continue on, excited to keep writing about hand-crafted wines, under-the-radar regions, and hopefully, some more breathtaking wine travels soon. In the meantime, here are the three most important things we’ve learned about Alpine wines over the past three years, to keep in mind for all of our future adventures:

1. Alpine wines are not necessarily “simple.”

When we first started exploring Alpine wines in earnest, we found that a lot of the discourse centered on terms such as “easy drinking” and “refreshing.” That’s fine, though one could argue that most wine regions offer at least some options that fit those criteria. But more importantly, as we’ve discovered the diverse wine grapes and styles across the Alps, we’ve found that “easy drinking” is a massive oversimplification. Think of Rèze made solera-style in the Swiss mountains, or Completer coaxed into potent, oxidative flavors. Or the intense reds, such as dark-fruited Mondeuse in Savoie, or powerful, long-lived Syrah in the Valais. And there was that 1984 Sauvignon Blanc from Alto Adige, which took what is so often a throwaway grape and transformed it into a stately, agreeable wine. Yes, the acidity in Alpine wines is refreshing, but it can also give these wines the fuel to go the distance and deliver more complex flavors over time.

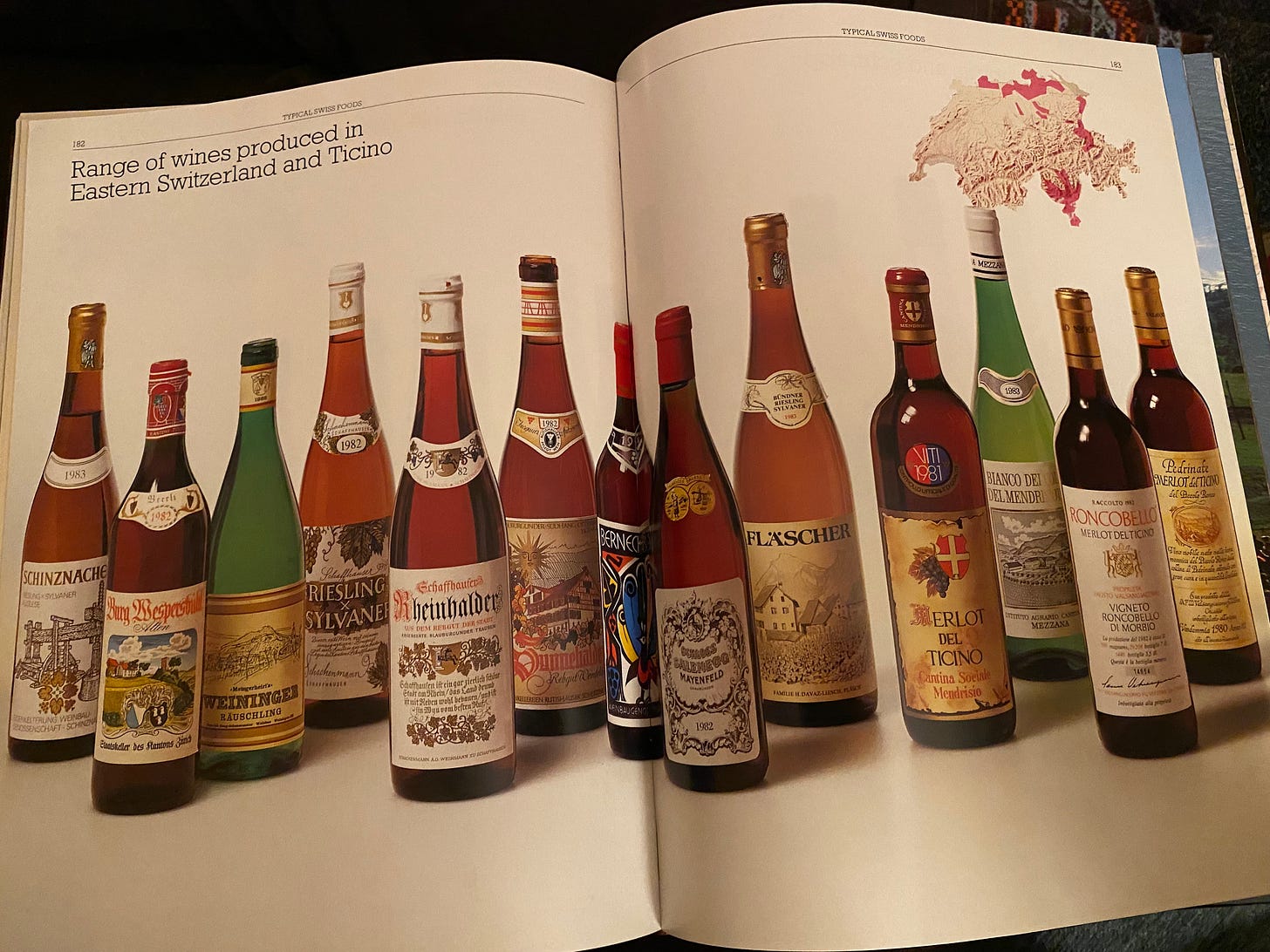

2. Swiss wines are not as reclusive as we previously believed.

They are elusive, yes–hard to find in the U.S. But that does not mean that Swiss winemakers resist being here. The common narrative about Swiss wines is that the domestic consumption in Switzerland is so strong that Swiss winemakers have little to no interest in exporting their wines anywhere, much less the States. Yet, after I was received so warmly as an American during my own travels to Swiss wine country, I realized this wasn’t necessarily true. Nearly all the winemakers I met with expressed an interest in seeing more of their wine exported, if not out of a hard financial incentive, then out of a desire to raise the profile of the work they’re doing. Indeed there are top-quality, boundary-pushing wines being made across Switzerland from the heights of Valais to the lakeshores of Zurich, which merit a place on the international stage. Swiss wines do require enthusiastic U.S. partners with the knowledge and the vision to position the wines to the U.S. market (and there is plenty of great work being done already - we’ll be publishing a directory for Swiss and Alpine wine resources in the coming weeks). Switzerland is the quintessential Alpine nation, and it’s important that more of their wines reach the shelves here.

3. What counts as an “Alpine” wine is an ongoing conversation.

Part of what made Alpine wines so exciting to us initially was that the concept encompassed many countries – Austria! Italy! France! Switzerland! Slovenia! Liechtenstein…okay, we have yet to feature a wine from Liechtenstein, but hopefully it will happen soon. But faced with this veritable cornucopia, we were excited to include as many of the wines as possible. We’ve since learned that in the absence of a formal definition of Alpine wines, what makes a wine “Alpine” is up for debate. Austria, so beloved for its Alpine culture, has most of its winemaking production concentrated in the east, closer to its Eastern European neighbors than to the Alpine peaks. We were compelled to ask ourselves if Piedmont is Alpine, yet the commune of Carema, administratively part of Piedmont, unambiguously makes mountain wines. More questions remain: does the Swiss Mittelland count? It’s home to the wines of Lakes Geneva, Zurich, Neuchâtel and Constance, and while flanked by the Alps, the area itself is technically a plateau.

Meanwhile some might argue that the wines of Bugey have more to do with the Jura mountains than with the French Alps. To answer these questions, one would need to decide if a wine’s Alpine qualities derive solely from their physical proximity to the peaks, or rather from the greater influence of the Alps, such as the soils that originated from the mountains or the distinct weather patterns (i.e. the Foehn). We imagine that an official definition of Alpine wines is forthcoming, and while we may not be the ones to author it, you can count on us to follow each step of the way.

Looking back on our first story, which includes Chardonnays of Savoie and Bugey plus a springtime risotto recipe:

And to learn more about us: